2024 is on track to be the worst year on record for cancer treatment wait times in Wales.

As the slippery slope of wait times becomes steeper, patients are bearing the brunt of a health system on its knees.

A year ago, the ‘Cambrian News’ started an award-nominated campaign highlighting the realities of what it’s like waiting for an MRI, a blood test, surgery that could save your life.

Numerous people came forward to share their stories.

One year on, patients are now scared to speak out in case it makes their wait times even greater.

In 2019, Welsh Government set the target to have 75 per cent of cancer patients treated within 62 days of cancer being first suspected by 2026.

Since setting that goal, no health board in Wales has met that target.

Between January and September 2024, 7,200 people waited more than two months to start treatment following an urgent referral.

This is having a huge impact on patient safety, health and wellbeing.

According to a Macmillan Cancer Support survey, two in three people being treated for cancer in the UK are now worried about pressures on the NHS affecting their chances of survival.

A spokesperson from West Wales Prostate Cancer Support Group, who is waiting for cancer treatment, was among those who did not want to be named: “Waiting times are now one of the main issues [discussed in the group] and this issue has increased.

“When you’ve been told you’ve got cancer, the next question everyone asks is, when does the treatment start?

“We all know the 62-day target isn’t being achieved, as patients it's concerning.

“When you’ve got cancer and waiting for treatment you wonder, how far is it advancing? Will it remain the same? How long will I have to wait?

“The wait is frustrating and it's not a great thing for your stress levels [a known carcinogen] and mental health.

“The 62-day target is never going to be accomplished.

“It’s the pressure on the NHS – with the best intentions of all people involved, you can only do so much in eight hours.

“It’s not just about cancer treatment; it’s the whole of the NHS that’s struggling.

“It’s difficult to allocate resources to carry out MRI scans let alone anything more invasive, it’s very much a balancing act and I wouldn’t like to be in their shoes.”

Though this group are struggling, some cancer types are waiting for longer than others – only 37 per cent with lower gastrointestinal cancer started their treatment within the 62-day window this year, with similar figures (38 per cent) for urological cancer and gynaecological cancer.

This may seem bad, but it’s made worse when compared to other countries – survival rates for colon and rectal cancer in women are only now reaching the levels Sweden and Norway achieved in the early 2000s.

For people like Claire’s partner Huw (pseudonyms), their wait wasn’t the availability of chemotherapy but booking an MRI to confirm the cancer was there in the first place.

Huw was diagnosed with colon cancer this August at Bronglais Hospital in Aberystwyth.

They had to wait over the target 62-days from when the cancer was first suspected by his GP in July to the October surgery that saved Huw’s life.

They recently got the incredible news that Huw now appears to be cancer-free.

Despite their wait being outside the 62-day target window, they were delighted by the efficient care from Bronglais staff.

Claire said: “I felt I put down a burden I didn't even know I was carrying when I heard the good news.

“Thank goodness for prompt action, both by him going to his GP and the hospital from then on.

“I was so scared about delays, but the only gap I really worried about was waiting for the MRI and then the results, as I knew they couldn't make a plan without that.

“That felt like an age but was less than two weeks from colonoscopy to MRI.

“The system is stretched and people are working hard in the NHS.

“The operation was knocked on by four days but ultimately everything went to schedule during a scary time and came to good.”

The government isn’t ignoring this, but Macmillan Cancer Support says their intervention doesn’t go far enough.

Kate Seymour, Macmillan Head of Advocacy, said: “[Jeremy Miles] the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care’s announcement of £50m funding to tackle the longest waits and help ease winter pressures on the healthcare system is welcome.

“But this is another missed opportunity to set out specific plans to reduce cancer waiting times, which are so urgently needed, and today’s figures show little improvement for those waiting for treatment.

“We are still waiting for [Mr Miles] to clearly lay out how he will tackle the completely unacceptable delays in Wales’ cancer services to ensure everyone affected by cancer, no matter who they are or where they live, has access to the support they need.”

Why are cancer treatment delays happening?

The NHS, on its knees from looking after patients during the Covid-19 pandemic, forced surgeons to cancel surgeries to cope with the sudden influx of Covid-19 patients, whilst others weren’t being diagnosed due to not being able to see a doctor.

The two years of pandemic pushed both potential diagnoses and treatments back- and the numbers have crept up ever since.

But Covid-19 delays aren’t the only issue.

The Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) 2023 workforce census on clinical oncologists describes “staffing shortages and funding constraints” at the forefront of treatment issues.

Nicky Thorp, Oncology Medical Director at RCR, said: “[There is a] 15 per cent shortfall of oncologists, a system strained beyond capacity.

“But beyond these figures lies a human impact: delayed appointments, restricted access to treatment, and the immense pressure placed on our colleagues.”

This represents a 185-person gap needed to deliver “required level of care”.

Wales has a 12 per cent shortfall in clinical oncologists, projected to grow to a 28 per cent shortfall by 2028 – which would make it the biggest shortfall in the UK.

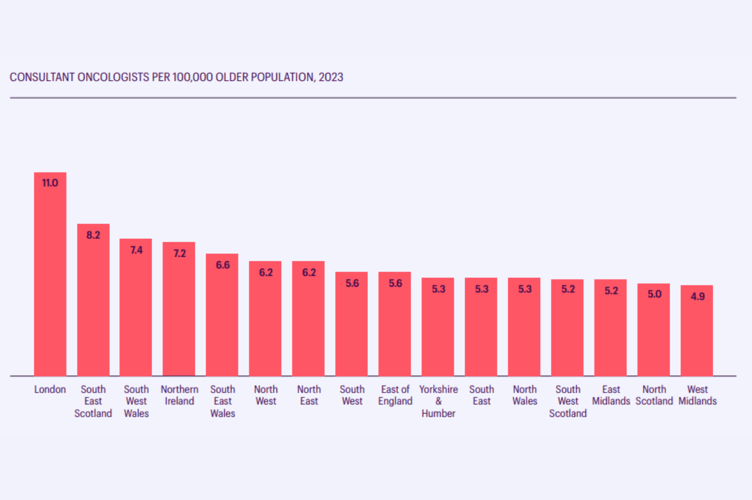

North Wales has the lowest number of oncologists per 100,000 older people in the country - 5.3 oncologists per 100,000 older people, whilst South East and West Wales have 6.6 and 7.4 per 100,000.

London, by comparison, had 11 oncologists per 100,000.

Staffing shortfalls are causing “routine delays” in patients starting treatment, whilst evidence indicates each four-week delay contributes to a 10 per cent chance of cure.

Wales has a “strong reliance on locum staff” (temporary staff) which as well as being costly, potentially impacts the long-term stability of the service”.

Patients are being referred across borders to be seen more quickly as postcode lotteries impact the care some receive, with some travelling over 100 miles to be seen.

But Wales isn’t alone in this crisis.

Across the UK, 95 per cent of cancer centres report delays to SACT (Systemic anti-cancer therapy – i.e. chemotherapy, immunotherapy) treatment and 82 per cent for radiotherapy treatment due to workforce shortages.

Four in five cancer centres are unable to keep up with the level of clinical demand with their existing workforce.

The poor performance affecting national targets isn’t just about lack of oncology staff – according to the RCR, it “demonstrates limited capacity in the whole treatment pathway including radiology, pathology, oncology and surgery”.

Many patients the Cambrian News spoke to were held up by MRI scans – with some going private to have the scan and diagnosis sped up.

Prostate cancer patient David (pseudonym) was referred for an MRI in June. Six months later, he is still waiting.

After numerous calls to chase this elusive scan, the radiology department at Glangwili Hospital said the scan would be “a good few months” and that they were not doing any “routine scans” - something he was alarmed to learn was the category his fell into.

In 2023 there was a 30 per cent shortfall in the radiology workforce – representing 1,962 radiologists missing from departments.

This is described as resulting in there not being enough radiologists to deliver “safe and effective levels of patient care”.

General hospital waitlists in Wales hit a record high five months in a row this summer, with 615,300 patients waiting for treatment – some waiting a year or two years for treatment to start.

The Welsh NHS Confederation representing health boards said these figures don’t show the ‘whole-system picture’, adding that pressures on GPs, community, mental health and social care were also stark, whilst over 1,500 people were stuck in hospital beds but ready to go home due to lack of social care.

The long-term impacts on staff

Across the UK, cancer centres are prioritizing urgent cases at the expense of the health and wellbeing of the staff working overtime.

83 per cent reported relying on goodwill – unpaid overtime – to manage the increasing demand for services.

Oncologists are asked to work longer hours to make up staff shortfalls resulting in doctors reporting they feel “unable to do their job to the best of their ability”.

Every single cancer centre in the UK is concerned about the morale, stress, and burnout of their workforce, with one stating: “Due to goodwill of the workforce, we mostly avoid any clinically significant delays, but this is at the cost of staff’s stress and working overtime.”

This can’t last forever and has an effect.

Two-thirds of oncologists who left the workforce in 2023 were under 60 years old, the median leavers' age dropping to 54 years, whilst 40 per cent of oncologists are now working under full-time hours.

The RCR describes this as “representing a significant loss of accumulated expertise that the NHS can ill afford”.

What’s going wrong?

According to RCR, there are “longstanding difficulties” in recruiting doctors to clinical oncology, attributed to lack of oncology on medical school syllabuses, lack of junior doctor exposure to the speciality, being put off by the requirement to study radiation physics and a perception of poor patient prognoses.

Cancer centres reported funding is the biggest barrier to recruiting more oncologists.

Though England’s latest funding will help expand the number of medical students, Nicky Thorp said by the time they graduate, the gap in oncologists will represent one-fifth of the workforce: “Future doctors will not solve today’s problem.

“We are 185 consultants short of what is needed to deliver an adequate level of care, yet the increasing prevalence of cancer and the need for more complex treatments shows no sign of slowing down.

“Meanwhile, more consultant oncologists are reducing their hours and leaving the profession at an earlier age than ever before.”

As Doctor Thorp states - cancer cases are on the rise and Cancer Research UK backs this up - the NHS is seeing more cancer patients than ever before.

According to the charity, the biggest risk factor for most cancer is ageing, with 90 per cent of cancer cases in those over 50.

Therefore as the UK life expectancy has increased over time, so has cancer rates.

Their analysis suggests that there will be around 3.75 million urgent cancer referrals in England in 2029, representing a 21 per cent increase from 2023.

How can the government fix this?

NHS standards of wait times were in the gutter before the pandemic – with wait times below acceptable levels since 2016.

There are no quick fixes, needing significant policy change, innovation and long-term investment.

Analysis from Health.org suggests addressing hospital bottlenecks to improve patient flow in, through and out of hospitals, investing in expanding hospital capacity by recruiting students, modernising buildings and replacing outdated equipment.

They suggest “reorienting the NHS towards prevention”, managing long-term illness effectively in the community to reduce hospital admissions – for this, they’ll also need properly funded adult social care.

They also suggest putting health as a focus for cross-government policy, not just the NHS, to reduce inequalities for “population-level action”.

RCR says workforce shortages limit centres from being able to adopt new efficient practices.

Despite this, Hywel Dda University Health Board only this year introduced a programme to speed up diagnosis rates for prostate cancer.

The “very successful” PROSTAD programme reduced the time between referral and diagnosis by 28 days for patients at Hywel Dda, speeding up MRI reporting times from eight days to one day.

In April 2022 Welsh Government released their strategy to reduce NHS wait times, and this November announced a £50,000 cash injection to the cause.

A Welsh Government spokesperson said: “We are committed to improving cancer waiting times and have recently announced £2m per year for a national cancer recovery programme.

“We have also provided a further £50m to health boards to increase capacity including more overtime working; more regional working and more outsourcing to the private sector – so more people can be seen.

“Our latest NHS Wales performance data showed we are now treating more and more people for cancer – more than 1,800 people started their first definitive cancer treatment during September.

“More than 15,800 patient pathways were opened during the month following a new suspicion of cancer and nearly 14,000 people were told the good news they did not have cancer.”